Rose and Corsage

I have spent days amid boxes of family memorabilia, the aftermath of cleaning out the storage locker. The boxes were taken from my mother's apartment when she died a decade ago; I thought I knew the the contents, but there were surprises.

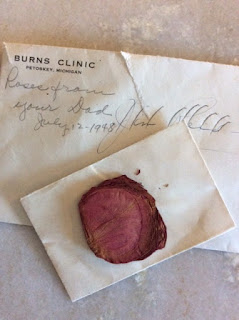

I found this envelope; the date is my birth. I opened it to find a second enclosure-sized envelope, and inside, a pressed rose:

The surprise was not that Dad, a man of courtly gestures, had sent his newborn roses, but that, over seventy years later, the bloom was still red; in that tiny envelope, time had stopped. I took a photo to commemorate its startling scarlet, then discarded the now-exposed fragment, along with yellowed news clippings, hand-drawn birthday cards, locks of baby hair: the things a mother saves.

Each box summoned benevolent ghosts—but for the next generation, the erosion of memory will dismiss them. What might have meaning when my children "go through Mama's things"? I kept Eleanor Roosevelt's invitation to tea at the White House, sepia photos of family homes and formally-dressed ancestors. I bought a pretty new box to hold the archive and trashed the battered, water-stained Hoover cases, themselves antiques.

In the bottom of one, I found two collections of silver; the first, part of my grandmother's Joseph Seymour set, ca.1915. (I had fun researching American hallmarks.) Grandma had divided it between her two daughters, and I knew one of Aunt Magdalen's grandsons had her half now. Pete replied immediately to say he'd take mine; I was pleased. The silver goes back to Chicago, its ancestral home.

But I had entirely forgotten about the second set, a dozen place settings and various serving pieces of my mother's trousseau silver, Stieff "Corsage", bought ca. 1935. I had only a faint memory of it; she mostly used her mother's silver, and stainless in the breakfast nook.

I wonder what drew her to "Corsage"'s floral extravaganza; it is not her usual restrained taste. The glamorous big sister Magdalen, who fly-fished in her old cocktail dresses and never wore a pair of glasses that were not jewelled, may have influenced her.

For preceding generations, the ritual of "choosing your pattern" was even more important than the wedding gown. I remember my sister's nerve-wracked decision in 1960: Reed & Barton Francis 1st, which I (silently) disliked: too heavy and formal.

When I married in 1971, though some girlfriends' mothers still hauled them into china departments, I found silver obsession as square as Lawrence Welk, and wanted care-free Dansk "Odin" stainless steel, which I still have:

Times change. After I unrolled the Marshall Field flannel pouches and polished the monogrammed pieces, I admired the highly-detailed repoussé and the soft glow of silver that for over eighty years had never seen the inside of a dishwasher.

We are using "Corsage" every day even though it accompanies just dishes, not Mom's china, which I gave to a friend a decade ago because it required hand-washing. I've decided to embrace the juxtaposition. (Either that or buy china.)

Like the red rose, it feels like a gift from beyond, sent with love and pride.

I found this envelope; the date is my birth. I opened it to find a second enclosure-sized envelope, and inside, a pressed rose:

The surprise was not that Dad, a man of courtly gestures, had sent his newborn roses, but that, over seventy years later, the bloom was still red; in that tiny envelope, time had stopped. I took a photo to commemorate its startling scarlet, then discarded the now-exposed fragment, along with yellowed news clippings, hand-drawn birthday cards, locks of baby hair: the things a mother saves.

Each box summoned benevolent ghosts—but for the next generation, the erosion of memory will dismiss them. What might have meaning when my children "go through Mama's things"? I kept Eleanor Roosevelt's invitation to tea at the White House, sepia photos of family homes and formally-dressed ancestors. I bought a pretty new box to hold the archive and trashed the battered, water-stained Hoover cases, themselves antiques.

In the bottom of one, I found two collections of silver; the first, part of my grandmother's Joseph Seymour set, ca.1915. (I had fun researching American hallmarks.) Grandma had divided it between her two daughters, and I knew one of Aunt Magdalen's grandsons had her half now. Pete replied immediately to say he'd take mine; I was pleased. The silver goes back to Chicago, its ancestral home.

But I had entirely forgotten about the second set, a dozen place settings and various serving pieces of my mother's trousseau silver, Stieff "Corsage", bought ca. 1935. I had only a faint memory of it; she mostly used her mother's silver, and stainless in the breakfast nook.

I wonder what drew her to "Corsage"'s floral extravaganza; it is not her usual restrained taste. The glamorous big sister Magdalen, who fly-fished in her old cocktail dresses and never wore a pair of glasses that were not jewelled, may have influenced her.

For preceding generations, the ritual of "choosing your pattern" was even more important than the wedding gown. I remember my sister's nerve-wracked decision in 1960: Reed & Barton Francis 1st, which I (silently) disliked: too heavy and formal.

When I married in 1971, though some girlfriends' mothers still hauled them into china departments, I found silver obsession as square as Lawrence Welk, and wanted care-free Dansk "Odin" stainless steel, which I still have:

Times change. After I unrolled the Marshall Field flannel pouches and polished the monogrammed pieces, I admired the highly-detailed repoussé and the soft glow of silver that for over eighty years had never seen the inside of a dishwasher.

We are using "Corsage" every day even though it accompanies just dishes, not Mom's china, which I gave to a friend a decade ago because it required hand-washing. I've decided to embrace the juxtaposition. (Either that or buy china.)

Like the red rose, it feels like a gift from beyond, sent with love and pride.

Comments

I've got to tackle the family memorabilia when I get home. I feel guilty because my mother is still alive and keeps track of such things.

Mme Là-bas: Quite an honour at 23! Does the family still have the tea set? Diving into the memorabilia was fun but frequently baffling as there were so many undated and uncaptioned photos. So while you have your mother, have her tell you who everyone is!

Marla: He was thrilled; this was just after the war, and he had been in the South Pacific for three years, in especially fierce fighting. Her penmanship held that strict cursive line all her life. But, people •wrote• much more then: letters, recipes, checks, notations on bills. I can go for many days without writing, how about you?

And the flatware! How ornate the patterns used to be. My Mother and Grandmother wanted me to collect a sterling pattern and encouraged me to choose one when I was far too young. It too was very ornate, a young girls fantasy. Fortunately, I later wised up, and chose...Dansk!

I have been going through similar treasures as I disperse my Mother-in-Law's estate. She has now moved to a nursing home.

In one box I found all of her 21st Birthday cards which I brought over to her on her birthday last month. She was both delighted and saddened as she recalled that all who had sent them were now gone!

As she had much of her mother's memorabilia I had such an enormous task. One wonderful find was a box of hand-typed short stories that her great, great aunt had written and had only been published once in newspapers over the years. They are rather along the line of Roald Dahl's short stories, so when I have time, I will re-type them and publish them, even if only for the State Library's collection and for family descendants.

Royleen: You can drive a tank over vintage Dansk’s European-made pieces. When manufacturing moved to Asia, somewhat less. The rose petal was eerie. (It must have been put in its envelope very shortly after she received them, but with no preservatives.)

Marla: One of our sons received a formal dispensation (in primary school) from having to write in cursive. To this day, nearly 25 yrs later, he only prints, very precisely. So I think of cursive writing as a sort of calligraphy.